After four years in Rwanda and DR Congo I was diagnosed with myalgic encephalomyelitis in Oct ‘08. Following two years in Malta, I moved to Melbourne, Australia where I found a doctor who diagnosed fructose intolerance and - eventually - Lyme Disease. My health improved, I returned to work, and next week I'm going back to my former life on the Big Island of Hawaii. Take a look at older posts (2004-2008) for stories & photos from Africa.

Thursday, March 30, 2006

Only two days left. The more I pack, the more there still seems to be left. I have to say goodbye to my wonderful cats, Safi and Jolie:

Saturday, March 25, 2006

Flowers

Downloading photos is going exceptionally fast today, so I'll take this opportunity to post some more! Can anyone tell me the name of this flower? I love it - it's one of the most amazing and intricate flowers I've ever seen. To see a full, high quality image of any of my photos, just double click on it.

Downloading photos is going exceptionally fast today, so I'll take this opportunity to post some more! Can anyone tell me the name of this flower? I love it - it's one of the most amazing and intricate flowers I've ever seen. To see a full, high quality image of any of my photos, just double click on it.

Packing

Today is the day I begin packing - that is, if I ever get around to it! I seem to have so much to do, and packing is not one of my favourite activities. I may go over to the National Museum later today with my housemate Rose, to pick up some Rwandan baskets to take with me. The museum is an easy 20 minute walk from here. It was built in the mid-80's and survived the war intact. It's a good, small museum with an interesting collection of artifacts and old photographs. Well worth a visit if you're in Rwanda. Rose, a medical doctor from the Philippines with 20 years of development experience, arrived in late January. I wish she'd come much sooner! We get on great, and she's a wonderful cook.

The National Museum of Rwanda, in Butare

My housemate Rose, demonstrating her cooking skills with a chicken

Today is the day I begin packing - that is, if I ever get around to it! I seem to have so much to do, and packing is not one of my favourite activities. I may go over to the National Museum later today with my housemate Rose, to pick up some Rwandan baskets to take with me. The museum is an easy 20 minute walk from here. It was built in the mid-80's and survived the war intact. It's a good, small museum with an interesting collection of artifacts and old photographs. Well worth a visit if you're in Rwanda. Rose, a medical doctor from the Philippines with 20 years of development experience, arrived in late January. I wish she'd come much sooner! We get on great, and she's a wonderful cook.

The National Museum of Rwanda, in Butare

My housemate Rose, demonstrating her cooking skills with a chicken

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

Bukavu

I just had to post this article from the New York Times - thanks so much to Ludovic in NYC for sending it to me!

A Real Getaway

By JAMES TRAUB

Published: March 19, 2006 (New York Times)

In the early hours of the morning, with the cool mountain breezes blowing, you can sit on a veranda in Bukavu and fancy that this seat of bloodshed and misery on the eastern border of Congo is, in fact, an Alpine retreat — and that Lake Kivu, a thoroughfare for smugglers and guerrillas, is, in fact, Lake Como. And once, in an unimaginably remote era, they were. The Belgians who colonized Congo called Bukavu the African Riviera, and in the steep green hills around Lake Kivu they built fine villas from which to watch the bathing hippos and the flamingos that thronged the shore.

The wildlife disappeared years ago, as did the tourists. Pretty much the only foreigners who now go to Bukavu are journalists like me or diplomats and aid workers trying to put an end to Congo's fratricidal wars and to palliate its misery. Today Bukavu is just another dusty Congolese provincial capital, an entrepôt through which smuggled timber and gold and coltan (a mineral from which cellphone chips are made) find their way to neighboring Rwanda. But it's still a fine thing to sit on a veranda with your beer — we are talking about evening here — and gaze out over Lake Kivu.

Bukavu has many bars and many vantage points over the lake, but to conjure up that vanished world, you must have your drink at Gerda's. You must stay there, too. A big, white, square building, formerly a private home, Gerda's is now a guesthouse that looks out on the lake; in front, an enormous gate protects it from the street. It has a well-stocked bar and a charming dining room, and there are nine guest rooms. Many of Bukavu's most eminent visitors, including Gen. Patrick Cammaert, the deputy force commander of the vast United Nations peacekeeping mission, will stay at no place but Gerda's. The resident foreign community, as well as the uppermost layer of Bukavan society, treats Gerda's as its canteen.

Gerda Dewitte, the owner of Gerda's and une femme d'un certain âge, is an exotic personage from the pages of Graham Greene — a dark-haired Belgian of voluptuous proportions, who sways along on high heels, the degree of oscillation increasing as the night draws on. Gerda cooks dinner — and she is an exceptional cook — but thereafter presides at the bar, where she is in her element. "Barman," she says imperiously. "Donnez-moi un verre." And the barman pours her another gin and tonic. Then, her necklace and bracelets glinting in the light, her ample poitrine perilously restrained, Gerda embarks upon a tale of woe, perhaps about how the local chaos has forced her to close her iron-roofing factory. The regulars drift back and forth between the bar and their companions. One night I saw a Frenchman bid farewell by joining Gerda behind the bar and giving her a tender slap on the bottom.

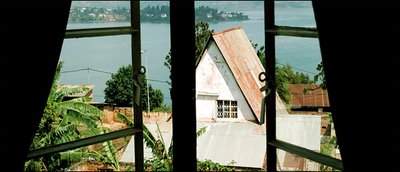

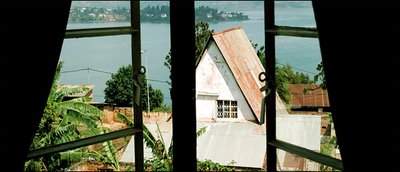

Gerda's has the feel of an immemorial establishment, but the truth is that it's only a year old. Gerda had been making a reputation for herself as the manager of the Welfare Club, the wonderfully named cafe-restaurant at the United Nations headquarters in Bukavu, when she decided to buy the house and bring her customers with her. As a hotelier, she is a novice, and while her put-upon staff does its best to keep things running, it is probably fair to say that the upstairs does not operate quite as smoothly as the dining room downstairs. When I arrived, there was no hot water in my room, and although Gerda graciously allowed me to use another room's shower, that hot water — indeed, all the water — ran out sometime between the soap and the shampoo. My room was quite satisfactory, even though its furnishings were limited to a king-size bed with a mosquito-net canopy and a little table pushed into a corner; the window looked out over a litter of yards and cottages and laundry lines to the shiny silver tray of the lake. At $60 or $70 a night, it was supremely reasonable.

Gerda's somewhat waspish disposition probably owes a good deal to the travails of her expatriate life. She and her husband, who is of Indian heritage, left Belgium for Rwanda in 1971, went to Congo six or seven years later and have lived there ever since. They have endured the kleptocratic regime of Mobutu Sese Seko, the almost nonstop civil war of 1996 to 2002 and the sacking of Bukavu by mutinous soldiers in 2004. Over the years, Gerda says, she has been looted "five or six times" — but she's always regrouped. The sense of lurking peril presumably accounts for Gerda's solicitude toward the authorities. She satisfied the local governor's demands for free food and drink until he was recalled to Kinshasa for corruption considered gross even by Congolese standards, and she counts the army's regional commander among her regular customers.

Virtually the best way to exit Bukavu, save by United Nations plane, is on a large boat, seating about 70 people, that makes a delightful two- to three-hour cruise up Lake Kivu to Goma, a larger city with commercial air connections. (The 60-mile drive over execrable roads is said to take five or six hours.) But when I went to buy a ticket for the boat one morning, I was told it had been sold out for days. I trooped back to Gerda's in despair. "Maybe," she said airily, "there is no boat tomorrow either, and you will stay one more night." Gerda seemed to think that I would take some solace in the fact that my loss would be her gain. I can't say that I did. But Gerda's heart, though hard, is by no means adamantine. Late that night, with the restaurant empty, the first hostess of Bukavu pointed to the mirrored shelves of the bar and said: "There are so many bottles that just sit here. Can I open one for you?" It was a noble gesture. I uncorked an Armagnac and decanted some into a snifter. Gerda, as I recall, drank another gin and tonic. We had a companionable chat. By next morning, it's true, I wanted nothing more than to leave Gerda's behind — and I did. But, like General Cammaert, I will never stay anywhere else in Bukavu.

I just had to post this article from the New York Times - thanks so much to Ludovic in NYC for sending it to me!

A Real Getaway

By JAMES TRAUB

Published: March 19, 2006 (New York Times)

In the early hours of the morning, with the cool mountain breezes blowing, you can sit on a veranda in Bukavu and fancy that this seat of bloodshed and misery on the eastern border of Congo is, in fact, an Alpine retreat — and that Lake Kivu, a thoroughfare for smugglers and guerrillas, is, in fact, Lake Como. And once, in an unimaginably remote era, they were. The Belgians who colonized Congo called Bukavu the African Riviera, and in the steep green hills around Lake Kivu they built fine villas from which to watch the bathing hippos and the flamingos that thronged the shore.

The wildlife disappeared years ago, as did the tourists. Pretty much the only foreigners who now go to Bukavu are journalists like me or diplomats and aid workers trying to put an end to Congo's fratricidal wars and to palliate its misery. Today Bukavu is just another dusty Congolese provincial capital, an entrepôt through which smuggled timber and gold and coltan (a mineral from which cellphone chips are made) find their way to neighboring Rwanda. But it's still a fine thing to sit on a veranda with your beer — we are talking about evening here — and gaze out over Lake Kivu.

Bukavu has many bars and many vantage points over the lake, but to conjure up that vanished world, you must have your drink at Gerda's. You must stay there, too. A big, white, square building, formerly a private home, Gerda's is now a guesthouse that looks out on the lake; in front, an enormous gate protects it from the street. It has a well-stocked bar and a charming dining room, and there are nine guest rooms. Many of Bukavu's most eminent visitors, including Gen. Patrick Cammaert, the deputy force commander of the vast United Nations peacekeeping mission, will stay at no place but Gerda's. The resident foreign community, as well as the uppermost layer of Bukavan society, treats Gerda's as its canteen.

Gerda Dewitte, the owner of Gerda's and une femme d'un certain âge, is an exotic personage from the pages of Graham Greene — a dark-haired Belgian of voluptuous proportions, who sways along on high heels, the degree of oscillation increasing as the night draws on. Gerda cooks dinner — and she is an exceptional cook — but thereafter presides at the bar, where she is in her element. "Barman," she says imperiously. "Donnez-moi un verre." And the barman pours her another gin and tonic. Then, her necklace and bracelets glinting in the light, her ample poitrine perilously restrained, Gerda embarks upon a tale of woe, perhaps about how the local chaos has forced her to close her iron-roofing factory. The regulars drift back and forth between the bar and their companions. One night I saw a Frenchman bid farewell by joining Gerda behind the bar and giving her a tender slap on the bottom.

Gerda's has the feel of an immemorial establishment, but the truth is that it's only a year old. Gerda had been making a reputation for herself as the manager of the Welfare Club, the wonderfully named cafe-restaurant at the United Nations headquarters in Bukavu, when she decided to buy the house and bring her customers with her. As a hotelier, she is a novice, and while her put-upon staff does its best to keep things running, it is probably fair to say that the upstairs does not operate quite as smoothly as the dining room downstairs. When I arrived, there was no hot water in my room, and although Gerda graciously allowed me to use another room's shower, that hot water — indeed, all the water — ran out sometime between the soap and the shampoo. My room was quite satisfactory, even though its furnishings were limited to a king-size bed with a mosquito-net canopy and a little table pushed into a corner; the window looked out over a litter of yards and cottages and laundry lines to the shiny silver tray of the lake. At $60 or $70 a night, it was supremely reasonable.

Gerda's somewhat waspish disposition probably owes a good deal to the travails of her expatriate life. She and her husband, who is of Indian heritage, left Belgium for Rwanda in 1971, went to Congo six or seven years later and have lived there ever since. They have endured the kleptocratic regime of Mobutu Sese Seko, the almost nonstop civil war of 1996 to 2002 and the sacking of Bukavu by mutinous soldiers in 2004. Over the years, Gerda says, she has been looted "five or six times" — but she's always regrouped. The sense of lurking peril presumably accounts for Gerda's solicitude toward the authorities. She satisfied the local governor's demands for free food and drink until he was recalled to Kinshasa for corruption considered gross even by Congolese standards, and she counts the army's regional commander among her regular customers.

Virtually the best way to exit Bukavu, save by United Nations plane, is on a large boat, seating about 70 people, that makes a delightful two- to three-hour cruise up Lake Kivu to Goma, a larger city with commercial air connections. (The 60-mile drive over execrable roads is said to take five or six hours.) But when I went to buy a ticket for the boat one morning, I was told it had been sold out for days. I trooped back to Gerda's in despair. "Maybe," she said airily, "there is no boat tomorrow either, and you will stay one more night." Gerda seemed to think that I would take some solace in the fact that my loss would be her gain. I can't say that I did. But Gerda's heart, though hard, is by no means adamantine. Late that night, with the restaurant empty, the first hostess of Bukavu pointed to the mirrored shelves of the bar and said: "There are so many bottles that just sit here. Can I open one for you?" It was a noble gesture. I uncorked an Armagnac and decanted some into a snifter. Gerda, as I recall, drank another gin and tonic. We had a companionable chat. By next morning, it's true, I wanted nothing more than to leave Gerda's behind — and I did. But, like General Cammaert, I will never stay anywhere else in Bukavu.

Sunday, March 19, 2006

Saturday morning

(I wrote this yesterday, but then our internet connection went down for the day before I could finish)

I walked into town this morning with a couple of VSO friends, to take some material to the tailor to have a blouse made. I've only had the material sitting in a drawer for two years, so with two weeks left to go, I thought I'd better do something with it while I'm in a place with a recommended tailor. He'll also hem a pair of too-long jeans for me. All for a very reasonable price.

Walking home through the leafy suburb of Taba where I live, I spotted a large eagle-like bird clinging upside down to the top of a broken street lamp. It was manoeuvering to pull out pieces of grass that must have been placed there by another bird. I looked up the bird in my 'Field Guide to the Birds of East Africa' as soon as I arrived home and discovered it was an African Harrier-Hawk, recognizable by the white band across its black tail. According to the book, these birds "regularly steal young from cavity nests like those of swifts and weavers, using their long flexible legs to probe for and grab nestlings." So maybe that's what the bird was doing when I spotted it. The birds here are a wonderfully impressive sight, and I always enjoy watching them circling the sky in the afternoons. The large black and white crows, on the other hand, are nasty scavengers. One of them attacked my cat, Safi, when he was a kitten, so naturally I'm not very fond of them! They also jump up and down on the tin roof making a serious racket.

I wanted to post more photos today, but for some reason I can't upload them. Next time!

(I wrote this yesterday, but then our internet connection went down for the day before I could finish)

I walked into town this morning with a couple of VSO friends, to take some material to the tailor to have a blouse made. I've only had the material sitting in a drawer for two years, so with two weeks left to go, I thought I'd better do something with it while I'm in a place with a recommended tailor. He'll also hem a pair of too-long jeans for me. All for a very reasonable price.

Walking home through the leafy suburb of Taba where I live, I spotted a large eagle-like bird clinging upside down to the top of a broken street lamp. It was manoeuvering to pull out pieces of grass that must have been placed there by another bird. I looked up the bird in my 'Field Guide to the Birds of East Africa' as soon as I arrived home and discovered it was an African Harrier-Hawk, recognizable by the white band across its black tail. According to the book, these birds "regularly steal young from cavity nests like those of swifts and weavers, using their long flexible legs to probe for and grab nestlings." So maybe that's what the bird was doing when I spotted it. The birds here are a wonderfully impressive sight, and I always enjoy watching them circling the sky in the afternoons. The large black and white crows, on the other hand, are nasty scavengers. One of them attacked my cat, Safi, when he was a kitten, so naturally I'm not very fond of them! They also jump up and down on the tin roof making a serious racket.

I wanted to post more photos today, but for some reason I can't upload them. Next time!

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

Talking about Bukavu

I woke up at 5:25 this morning - I wish I could do that every day! We have a pink streaked dawn, which means it will probably rain again today. I'm not complaining. Everyone needs the rain. Back in early February it was hot, hot, hot, with not a dark cloud in sight. Now I wear a thick fleece jacket to work. On 1st April I head back to Amsterdam, where it'll be even colder! Although I expect spring will be on its way. Since I've learned that I'll soon be moving to Bukavu it seems like almost everyone I talk to has a Bukavu connection; they've either visited, lived there, or have relatives there. I've been told that Bukavu is a bit cooler than here; I've also been told by just as many people that it's warmer than here. Yesterday I took a look at the BBC weather web site: for this week at least, Bukavu has more rain than here and is a couple of degrees cooler.

A week ago one of the best musicians in the world died: Ali Farka Toure from Mali. If you've never heard his divine music, now is the time to open your ears and take a listen! His music is well known and CDs easily available from amazon.com or many other places. I have the Talking Timbuktu album (thank you, Nicole!), and I've read an excellent review of the most recent one: In the Heart of the Moon.

Since I announced my move to Bukavu the messages have been flooding in. It's really wonderful to hear from you and catch up with what is going on in your life - thank you for writing!

These boys are collecting palm kernels along the street in Gisenyi next to Lake Kivu. Their mother will use the kernels in cooking a local dish. Bukavu lies on the other end of this long, narrow lake.

I woke up at 5:25 this morning - I wish I could do that every day! We have a pink streaked dawn, which means it will probably rain again today. I'm not complaining. Everyone needs the rain. Back in early February it was hot, hot, hot, with not a dark cloud in sight. Now I wear a thick fleece jacket to work. On 1st April I head back to Amsterdam, where it'll be even colder! Although I expect spring will be on its way. Since I've learned that I'll soon be moving to Bukavu it seems like almost everyone I talk to has a Bukavu connection; they've either visited, lived there, or have relatives there. I've been told that Bukavu is a bit cooler than here; I've also been told by just as many people that it's warmer than here. Yesterday I took a look at the BBC weather web site: for this week at least, Bukavu has more rain than here and is a couple of degrees cooler.

A week ago one of the best musicians in the world died: Ali Farka Toure from Mali. If you've never heard his divine music, now is the time to open your ears and take a listen! His music is well known and CDs easily available from amazon.com or many other places. I have the Talking Timbuktu album (thank you, Nicole!), and I've read an excellent review of the most recent one: In the Heart of the Moon.

Since I announced my move to Bukavu the messages have been flooding in. It's really wonderful to hear from you and catch up with what is going on in your life - thank you for writing!

These boys are collecting palm kernels along the street in Gisenyi next to Lake Kivu. Their mother will use the kernels in cooking a local dish. Bukavu lies on the other end of this long, narrow lake.

Thursday, March 02, 2006

Losing colleagues

It's always good to hear from those of you who actually read my blog; and your messages serve as a bit of a nudge to get me writing again! So today, thank you to Charles in Cameroon for giving me that incentive to get my hands moving again on the keyboard.

And for those of you who look to my blog for reading suggestions, this is what I'm enjoying right now: "Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything" by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner. It's been reviewed far and wide (well, in The Guardian Weekly, anyway!). Fascinating stuff. Easily as good as the murder mysteries I don't usually admit to reading.

And now to my heading for today. Tuesday this week was the last day at work for nine guards at our house and office here in Butare, and for around twenty guards based in Kigali. Some had worked in this job for eleven years, but they have lost their jobs to a private security company. So we now have guards wearing uniforms, carrying batons and walkie-talkies (but thankfully no weapons). It was sad to say goodbye to the guards who were colleagues, and who, inevitably, I had come to know. From those who speak French or English I had learned about their children, their aspirations, their hardships. Some have completed secondary school and will have a chance at finding other work; others have not, and in a country where maybe only 15% of the population has paid employment, the loss of this job will have a major impact on the well-being of their families. Our day guard at the house also doubled as our gardener, and, on a selfish note, he will be missed! Since I don't have the time to do all the work involved in taking care of my chickens, they were the first to go: given away. That means no more fresh, free range eggs. And if you want to know if you can taste the difference between a mass-produced egg and a fresh free-range egg, the answer is an unequivocal 'yes'!

Muchy sadder was the loss of a colleague from our Ruhengeri office, Tatien Dusabeyezu, who died recently of a brain tumour. He was friendly and outgoing with a great sense of humour. A former driver from the same office is now in hospital, also apparently with a brain tumour. And a Dutch friend and neighbour who recently returned to the Netherlands when feeling unwell, was also diagnosed with a brain tumour. I have to assume this is all a very sad coincidence.

The good news (I had to find something good to end this with!) is that it has been raining here for the past two weeks - just in time for people to begin planting seeds for this season. Now we pray that the rain will continue! For information on the food shortages affecting various areas of Africa, go to www.fews.net, a web site sponsored by USAID giving detailed information and maps.

Tatien Dusabeyezu giving a lively presentation at our September 2005 Programmes Meeting

It's always good to hear from those of you who actually read my blog; and your messages serve as a bit of a nudge to get me writing again! So today, thank you to Charles in Cameroon for giving me that incentive to get my hands moving again on the keyboard.

And for those of you who look to my blog for reading suggestions, this is what I'm enjoying right now: "Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything" by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner. It's been reviewed far and wide (well, in The Guardian Weekly, anyway!). Fascinating stuff. Easily as good as the murder mysteries I don't usually admit to reading.

And now to my heading for today. Tuesday this week was the last day at work for nine guards at our house and office here in Butare, and for around twenty guards based in Kigali. Some had worked in this job for eleven years, but they have lost their jobs to a private security company. So we now have guards wearing uniforms, carrying batons and walkie-talkies (but thankfully no weapons). It was sad to say goodbye to the guards who were colleagues, and who, inevitably, I had come to know. From those who speak French or English I had learned about their children, their aspirations, their hardships. Some have completed secondary school and will have a chance at finding other work; others have not, and in a country where maybe only 15% of the population has paid employment, the loss of this job will have a major impact on the well-being of their families. Our day guard at the house also doubled as our gardener, and, on a selfish note, he will be missed! Since I don't have the time to do all the work involved in taking care of my chickens, they were the first to go: given away. That means no more fresh, free range eggs. And if you want to know if you can taste the difference between a mass-produced egg and a fresh free-range egg, the answer is an unequivocal 'yes'!

Muchy sadder was the loss of a colleague from our Ruhengeri office, Tatien Dusabeyezu, who died recently of a brain tumour. He was friendly and outgoing with a great sense of humour. A former driver from the same office is now in hospital, also apparently with a brain tumour. And a Dutch friend and neighbour who recently returned to the Netherlands when feeling unwell, was also diagnosed with a brain tumour. I have to assume this is all a very sad coincidence.

The good news (I had to find something good to end this with!) is that it has been raining here for the past two weeks - just in time for people to begin planting seeds for this season. Now we pray that the rain will continue! For information on the food shortages affecting various areas of Africa, go to www.fews.net, a web site sponsored by USAID giving detailed information and maps.

Tatien Dusabeyezu giving a lively presentation at our September 2005 Programmes Meeting

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)