I just had to post this article from the New York Times - thanks so much to Ludovic in NYC for sending it to me!

A Real Getaway

By JAMES TRAUB

Published: March 19, 2006 (New York Times)

In the early hours of the morning, with the cool mountain breezes blowing, you can sit on a veranda in Bukavu and fancy that this seat of bloodshed and misery on the eastern border of Congo is, in fact, an Alpine retreat — and that Lake Kivu, a thoroughfare for smugglers and guerrillas, is, in fact, Lake Como. And once, in an unimaginably remote era, they were. The Belgians who colonized Congo called Bukavu the African Riviera, and in the steep green hills around Lake Kivu they built fine villas from which to watch the bathing hippos and the flamingos that thronged the shore.

The wildlife disappeared years ago, as did the tourists. Pretty much the only foreigners who now go to Bukavu are journalists like me or diplomats and aid workers trying to put an end to Congo's fratricidal wars and to palliate its misery. Today Bukavu is just another dusty Congolese provincial capital, an entrepôt through which smuggled timber and gold and coltan (a mineral from which cellphone chips are made) find their way to neighboring Rwanda. But it's still a fine thing to sit on a veranda with your beer — we are talking about evening here — and gaze out over Lake Kivu.

Bukavu has many bars and many vantage points over the lake, but to conjure up that vanished world, you must have your drink at Gerda's. You must stay there, too. A big, white, square building, formerly a private home, Gerda's is now a guesthouse that looks out on the lake; in front, an enormous gate protects it from the street. It has a well-stocked bar and a charming dining room, and there are nine guest rooms. Many of Bukavu's most eminent visitors, including Gen. Patrick Cammaert, the deputy force commander of the vast United Nations peacekeeping mission, will stay at no place but Gerda's. The resident foreign community, as well as the uppermost layer of Bukavan society, treats Gerda's as its canteen.

Gerda Dewitte, the owner of Gerda's and une femme d'un certain âge, is an exotic personage from the pages of Graham Greene — a dark-haired Belgian of voluptuous proportions, who sways along on high heels, the degree of oscillation increasing as the night draws on. Gerda cooks dinner — and she is an exceptional cook — but thereafter presides at the bar, where she is in her element. "Barman," she says imperiously. "Donnez-moi un verre." And the barman pours her another gin and tonic. Then, her necklace and bracelets glinting in the light, her ample poitrine perilously restrained, Gerda embarks upon a tale of woe, perhaps about how the local chaos has forced her to close her iron-roofing factory. The regulars drift back and forth between the bar and their companions. One night I saw a Frenchman bid farewell by joining Gerda behind the bar and giving her a tender slap on the bottom.

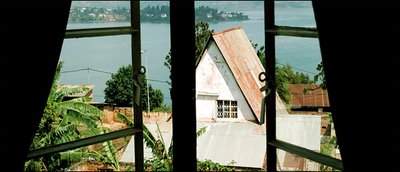

Gerda's has the feel of an immemorial establishment, but the truth is that it's only a year old. Gerda had been making a reputation for herself as the manager of the Welfare Club, the wonderfully named cafe-restaurant at the United Nations headquarters in Bukavu, when she decided to buy the house and bring her customers with her. As a hotelier, she is a novice, and while her put-upon staff does its best to keep things running, it is probably fair to say that the upstairs does not operate quite as smoothly as the dining room downstairs. When I arrived, there was no hot water in my room, and although Gerda graciously allowed me to use another room's shower, that hot water — indeed, all the water — ran out sometime between the soap and the shampoo. My room was quite satisfactory, even though its furnishings were limited to a king-size bed with a mosquito-net canopy and a little table pushed into a corner; the window looked out over a litter of yards and cottages and laundry lines to the shiny silver tray of the lake. At $60 or $70 a night, it was supremely reasonable.

Gerda's somewhat waspish disposition probably owes a good deal to the travails of her expatriate life. She and her husband, who is of Indian heritage, left Belgium for Rwanda in 1971, went to Congo six or seven years later and have lived there ever since. They have endured the kleptocratic regime of Mobutu Sese Seko, the almost nonstop civil war of 1996 to 2002 and the sacking of Bukavu by mutinous soldiers in 2004. Over the years, Gerda says, she has been looted "five or six times" — but she's always regrouped. The sense of lurking peril presumably accounts for Gerda's solicitude toward the authorities. She satisfied the local governor's demands for free food and drink until he was recalled to Kinshasa for corruption considered gross even by Congolese standards, and she counts the army's regional commander among her regular customers.

Virtually the best way to exit Bukavu, save by United Nations plane, is on a large boat, seating about 70 people, that makes a delightful two- to three-hour cruise up Lake Kivu to Goma, a larger city with commercial air connections. (The 60-mile drive over execrable roads is said to take five or six hours.) But when I went to buy a ticket for the boat one morning, I was told it had been sold out for days. I trooped back to Gerda's in despair. "Maybe," she said airily, "there is no boat tomorrow either, and you will stay one more night." Gerda seemed to think that I would take some solace in the fact that my loss would be her gain. I can't say that I did. But Gerda's heart, though hard, is by no means adamantine. Late that night, with the restaurant empty, the first hostess of Bukavu pointed to the mirrored shelves of the bar and said: "There are so many bottles that just sit here. Can I open one for you?" It was a noble gesture. I uncorked an Armagnac and decanted some into a snifter. Gerda, as I recall, drank another gin and tonic. We had a companionable chat. By next morning, it's true, I wanted nothing more than to leave Gerda's behind — and I did. But, like General Cammaert, I will never stay anywhere else in Bukavu.

No comments:

Post a Comment